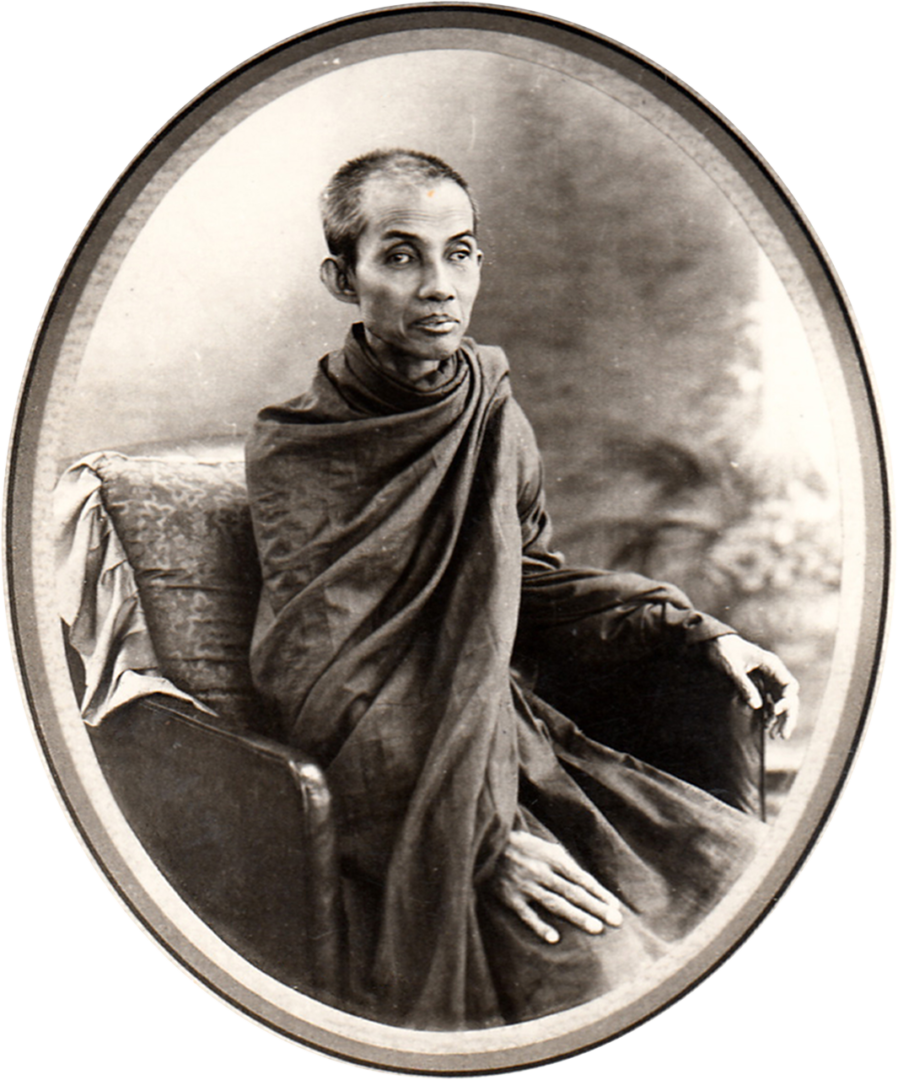

HRH Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa

UNESCO Eminent Personality of the World 2021

His Royal Highness Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa

His Royal Highness Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa was born on 12 April 1860 in the Royal Palace, Bangkok, and he passed away on 2 August 1921, also in Bangkok. His birth name was Prince Manussanāga and he was the 47th child of King Rama IV (King Mongkut). As was the tradition at the time, he received his education in the palace. He was brought up by his aunt, Princess Varasethasuda, a formidable figure who left a lasting impression on him, teaching him arithmetic and how to write Thai verse and reading with him history, poetry, and religious books. He learned to read, write, and speak English from English and Scottish tutors. For several months, following Thai tradition, he was ordained as a novice-monk when he was fourteen. After this he enjoyed life in the world as a young layman, but he was drawn closer and closer to the Buddhist religion. His uncle, Prince Pavares, a man of exemplary conduct, was the Supreme Patriarch, the chief monk of the monastic order. Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa regularly visited him in his temple; as a young prince, he drew close to him and learned from him poetry, astrology, and Buddhist scripture.

After these experiences of the life of a young prince, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa’s earlier encounter with the ascetic life, the influence of his aunt in the palace and of his uncle, Supreme Patriarch Pavares, in the temple, plus his natural proclivity to the Dhamma, led him to take full ordination as a Buddhist monk in 1879 at the age of twenty-two. He remained a monk for the rest of his life.

His half-brother, Rama V (Chulalongkorn) was King of Siam, a flourishing kingdom that managed to maintain its independence while most of Asia fell under the control of the expansionist European colonial powers. Rama V saw the urgent need to turn the ancient kingdom into a modern nation that could march with the times as an independent and progressive member of the world community. He initiated broad administrative, legal, and social reforms to carry this out. At his elder brother’s request, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa joined in this project and became one of the key figures in the transformation of Thai culture and society that bridged the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He took on this role already, before his ordination, when he spent two years as a legal secretary to King Chulalongkorn, helping the King to pursue his policy of reform of the government departments and the legal system. After his ordination his role was especially prominent in education and culture and in the foundation of the social and human sciences.

The royal government wanted to introduce primary and secondary schooling throughout the country. The King entrusted Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa to modernize the educational system, and Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa developed both the monastic and the secular educational systems. For monastic education, this meant developing national standards of study, curriculum and examination and instituting these throughout the kingdom. Today we take universal education and its trappings—textbooks, curricula, and examinations—for granted. It is hard to imagine now the degree of patience and perseverance that Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa’s task demanded. Up until Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa undertook these reforms, the traditional system of education was centred around individual teachers and their communities, a system of hundreds of years’ standing that had none of these trappings. Overcoming considerable resistance to change from within the system, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa developed new curricula and composed textbooks that remain in use up to the present day. He presided over the foundation of the Mahamakut Buddhist University (1893) and the spread of monastic and lay education in the provinces. He wrote that ‘Secular and religious learning flow in the same channel. Each will sustain the burdens of the other so that both may move forward and progress.’ He read about geography, history, psychology, and linguistics, and integrated them into his thought and works. For primary school children he wrote about the Five Precepts—the basic moral guidelines for lay people. His practical handbook for those ordained as monks, Instructions for New Ordinands (Navakovāda), has been used throughout the country up to the present.

How could primary and secondary education be developed, when the government had limited funds and people power? Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa astutely took advantage of the thousands of temples that already existed throughout the country, and began to open schools on temple land. Since the temples were the community centres and the centres of traditional knowledge and education, he wanted modern education to be paired with traditional.

Thai Buddhism is monastic. Individuals (males only) ordain as monks and spend their time in temples or monasteries. In terms of administration, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa initiated the first Sangha Act in 1902 to centralize control of Buddhist monasticism. This meant streamlining local practice and instituting a hierarchical authority across the country.Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa himself spent his life as a Buddhist monk who scrupulously followed the monastic rules. But this did not wall him in. He travelled the kingdom to learn about the condition of society, and his accounts of his journeys remain literary masterpieces. From 1910 to 1921 he was the tenth Supreme Patriarch of Thailand.

Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa’s erudition on ancient language and archeology was well manifested in his pioneer work on interpretation and commentary on the discovery of the Buddha’s bone relics by William Claxton Peppe, a British colonial engineer and landowner of an estate at Piprahwa near the Nepalese border and the Buddha’s birthplace at Lumbini, Nepal in January 1898. Soon after the discovery, the bone relics from Peppe´s excavation were offered by the government of India to the King of Siam, who shared them with Buddhist communities in many other countries with close advise from Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa. On this matter, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa even published a text book on studying Brahmi script, the oldest Asokan script of India for the first time in Buddhist countries.

Moreover, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa published a text book for learning the universal Pali script called ‘Ariyaka’ which was invented by his father, King Mongkut and once used internationally among Buddhist countries just like English in these days.[i]

Historian David K. Wyatt has described him as ‘the leading intellectual of his generation in Siam’. Without ever travelling abroad, through discussion and study he gained a thorough knowledge of the works of world thinkers and put this new knowledge into practice in his daily life and social programmes.

His legacy as a man of letters is impossible to sum up in a few words. He wrote one of the earliest autobiographies in Thai literature. Written from 1915, it is a fascinating personal account of how he was raised in the palace—the intellectual development of a young prince in relation to the ascetic life and the problems faced by Siamese society that is a remarkable resource for the social history of the times. His new curricula for Pali and Buddhist studies changed the style of textbooks, introducing printed books and modern ideas. He wrote for the monastic schools and for lay people. His Vinayamukha in three volumes is an ‘Entrance to the Vinaya’, that is, an introduction to the monastic duties, ceremonies, and regulations that has been a classic for one hundred years. In 1894, he founded the journal Dhammacaksu, ‘Eye of the Dhamma’, the first journal of Thailand which continues to this day—over a hundred years. His interests were multidisciplinary, engaging in many fields beyond straightforward monastic affairs—he studied and wrote about history and archaeology, ethics and social conduct.

Though he lived to be only 61, Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa was an amazingly prolific intellectual, scholar, and writer. A study of the catalogues of all the world’s major libraries reveals that the Prince published 484 items, of which 440 were books. Many of his works are available in English translation. His publications have also been translated into French, Khmer, and Indonesian. In the catalogues of the world’s research libraries there are also 244 books or monographs which mention the work of Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa as a subject.

In summary looking at his total body of work, he produced six books on Pali grammar, one text for studying English, 12 texts related to Buddhist curriculum, 75 texts on Buddhist teaching, 22 articles on Buddhist teaching, 41 articles on general morals, 36 articles on education, 22 articles on ancient history, 11 articles on liberal education, 71 articles on the Buddhist monkhood, 12 articles on the Pali language, translation of 47 Buddhist curricula, 21 explanations of Buddhist curricula, and 13 books clarifying the Pali language, He also translated volumes from Pali, Sanskrit, English, and French into Thai, broadening his knowledge of the broader world beyond Siam.

Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa had been raised royally with the best of advantages. He made the best of these to become a prominent intellectual in the court and later in the monastic circles. He did not use his charmed position for his own benefit, but dedicated his career to the benefit of the country. He worked diligently—so hard that his health suffered in latter years—to modernize Siam in a challenging period when the world’s social, economic, and political systems were changing rapidly, and Siam’s cherished independence was threatened by encroaching colonial powers. Advances in communications brought the world closer together more rapidly than ever before, accelerating social change and broadening its scope. Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa was able to keep pace with this change and to apply wisdom to find intelligent solutions to the problems that he confronted.

Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa stands out as an extraordinary and positive figure in Thailand’s age of transition to world modernity. His dynamic participation, his sincerity and honesty in all that he undertook, and his selfless dedication to education and to the improvement of administration of both the monastic and social order had a profound and lasting impact at many levels of Siamese society. We live today in an age of increasing materiality and self-assertion. We need to remind ourselves of people like Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa who was content to live simply and frugally and who selflessly and indefatigably dedicated his life to the advancement of knowledge and society.

It is worthwhile to celebrate Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa’s exemplary life and deeds and to make them better known worldwide as an outstanding example of an intelligent life spent in the service of humanity. We recommend His Royal Highness Prince Vajirañāṇavarorasa as a UNESCO Important Person of the world on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his death.

[i] Sakya, Anil Venerable,2012. ‘King Mongkut’s invention of a Universal Pali Script’ in How Theravāda is Theravāda? Exploring Buddhist Identities edited by Peter Skilling, Jason A. Carbine, Claudio Cicuzza, Santi Pakdeekham. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Education

Culture

Social & Human Sciences

Written Work

Prince-Patriarch Vajirañāṇavarorasa's Proverbs

UNESCO Eminent Personality of the World 2021

"Timing is Key to Success"

"Patience Prohibits Abruptions."

"Moderation always bears Good Results."

"Moral shame and Moral dread indeed Protect the World."